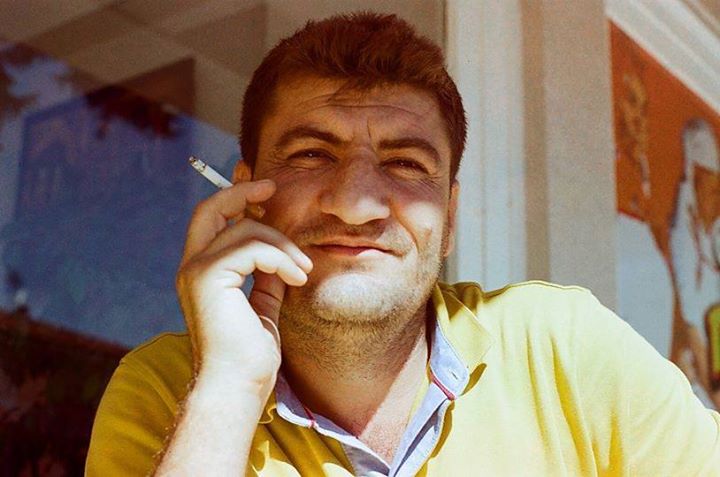

Thanks in large part to the work of Raed Fares, the town of Kafranbel, Syria became the creative centre and conscience of the revolution against Bashir al-Assad.

Raed played a crucial role in the non-violent opposition movement by kick-starting the country’s first independent media and suffered several assassination attempts before he was finally killed on 23 November, 2018. His friend and fellow activist Hamoud Juneid also died during the attack, in which unknown assailants in a van shot at the two men with machine guns.

A journalist and community organiser, Raed was skilled at transmitting news and analysis to the wider world, often pointing out the parallels between events abroad and at home with tweets such as “We stand in solidarity with the oppressed who cannot breathe #blacklivesmatter.” He was published by a variety of international outlets and described the impetus for his human rights work in a recent editorial for the Washington Post.

I started Radio Fresh in 2013 as a local station based in my home town of Kefranbel to reach audiences in Idlib, Aleppo, and Hamah provinces. It was crucial that the Syrian people receive independent news about what was going on in their country, and there was no other station of that kind at that time.

As a journalist and activist, I felt I had a duty to counter the fundamentalist narratives that are spreading among people who have no other source for hope in our war-torn homeland.

The Syrian conflict escalated in part because terrorists are winning an ideological battle for Syria’s soul. The people in villages like Kefranbel, especially the children, have been living in an environment of war, hate, violence and scenes of bloodshed for more than six years. In the absence of peaceful, democratic political voices, terrorists have been able to convince Syria’s vulnerable youth that violence and destruction can somehow pave the way to stability. Civil society groups and independent media are working tirelessly to oppose these messages – in ways that resonate with local audiences. Syria’s democratic future relies on our success.

An interview with the BBC explored the way in which humour fuelled Raed’s activism. Explaining his radio show’s odd audio tracks, he said “They tried to force us to stop playing music on air. So we started to play animals in the background as a kind of sarcastic gesture against them.” He even joked about a gunshot to the chest that nearly killed him: “I still have trouble breathing, but my doctor says my lungs should be no problem because of the size of my nose.” However, Raed was intimately acquainted with death and fully understood how risky his work was. Later on in the interview he said “They’ve tried to kill me five times already. If it happens, it happens. But they haven’t succeeded yet. I try to survive, but if I can’t, it’s OK.”

The lowest point in his life came when one of his closest friends was killed and another severely injured by a bomb. Fares admitted that he nearly took his own life in the days that followed, but eventually became more determined than ever to carry on.

“We started the revolution together and were all aware that we faced the same risks,” he said “That means that my life isn’t more expensive than my friends who lost their lives.”

Fares’ last post was the video of a protest in his home-town, captioned with the words “The people of Kafranbel are in Huriyah [Freedom] Square and voices are chanting: The people want the downfall of the regime. We started this in 2011 and we are continuing on. Our loyalty to the martyrs and detainees has increased our determination.”