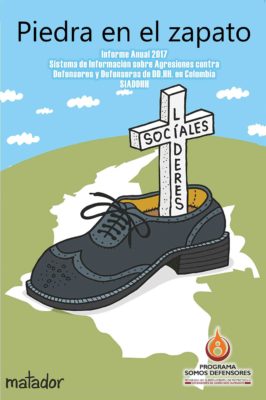

“Piedra en el Zapato” – “Stone in the Shoe”.

Bogotá D.C. March 1, 2018 – Communications Programma Somos Defensores

Programma Somos Defensores Annual Report for 2017 looks at the critical situation for HRDs in Colombia.

Yes, peace brought less general violence in Colombia but instead the violence focused on social leaders and human rights defenders (HRDs). 2017 was a sad year considering the 32.5% increase in killings which resulted in the deaths of 106 HRDs while 2018 seems likely to continue the same trend with 18 killings of HRDs in January alone. The government continues to issue decrees that are never implemented and we still don’t know if the new government will shelve them. Social leaders in rural areas of the country are facing another year of targeted violence that shows no sign of abating.

This report is an analysis of a year that we do not want to repeat.

Download the report HERE

Watch our launch video HERE

2017 was a year in which the armed confrontation and its endless list of victims ceased to be daily news. The signing and beginning of the implementation of the Peace Agreements, brought about a substantial decrease in deaths; However, in the midst of this positive trend, another phenomenon became increasingly evident and showed an unacceptable increase: the murder of social leaders and HRDs in Colombia.

Despite the peace process there are a number of trends which continue to put the lives of HRDs at risk: HRDs continue to be the target of systematic violence due to, newly emerging conflicts, : the absence of a state presence in some areas, the unbridled focus on the extraction of natural resources; drug trafficking; the fight for the land; hate crimes; corruption; the struggles of other guerrilla groups of paramilitary descent, the growing presence of Mexican drug cartels and organised crime in ex-FARC areas, among others.

Undoubtedly, 2017 was the most critical year in the eight year term of President Juan Manuel Santos. This level of violence against HRDs is very serious and besides worrying the human rights community, researchers, the international community and sectors sensitive to the phenomenon, it has become a STONE IN THE SHOE (Piedra em el Zapato) of the Santos Government in the context of its policy to create the conditions for peace. And at the same time HRDs in Colombia are also the “STONE IN THE SHOE” for those who want to seize control of the national territory, using any available means.

During 2017, 560 HRDs were attacked, which figure included 106 killings (32.5% increase), 370 threats, 50 attacks, 23 arbitrary detentions, 9 judicial proceedings and 2 thefts of sensitive information. Looking at the figures for the killings we can see that there was progress in 30% of the cases. In relation to killings of HRDs this report includes a comparative analysis of the various reports produced by social and human rights organisations in 2017. In this analysis we have found considerable convergence in the findings across all these reports in relation to, the number of killings of HRDs, the pattern of the killings, the profile of the leaders targeted, the areas with the highest number of killings and the identity of the alleged perpetrators.

The report also examines a number of issues that are central to the protection of HRDs, including:

-

the role of the new legal provisions derived from the Havana Agreement on issues for the protection of defenders that have not yet been implemented and remain on paper;

-

the failure of the Colombian Government to take preventive action;

-

the lack of progress in the Prosecutor’s office that is still not in a position to meet the demand for justice;

-

the slow response of state bodies in taking pre-emptive action before the massacre of defenders

-

the ongoing and constant stigmatisation of these activists that with the upcoming elections will raise the level of danger they face in every corner of the country.

But despite such bad news, the report also notes concrete proposals to get the country out of this mess and start looking for joint solutions to a problem that far from diminishing, is increasing daily and seems to want to stay for a long time. There is an urgent need to alert candidates to the Presidency so that, if they are elected, they don’t simply file this vital issue for the future of the country away in a drawer.

For the publication of this report we have counted on the invaluable collaboration of several prominent national cartoonists, who in solidarity have used their images to portray the reality faced by the country’s social leaders. So a special thanks to Julio César González – MATADOR, Pablo Pérez – ALTAIS, Carlos Arturo Romero, Marco Pinto, Harold Trujillo – CHÓCOLO and Cecilia Ramos – LA CHÉ. Your work may be appreciated in the report.

The complete figures on attacks against human rights defenders in Colombia for 2017 and other periods can be consulted at www.somosdefensores.org

FOR FURTHER INFORMATION PLEASE CONTACT:

Coordinador Comunicaciones, Incidencia y Sistema de Información – SIADDHH

@SomosDef

Cel. (057) 3176677053

Tel.(057 1) 2814010

www.somosdefensores.org

Bogotá – Colombia