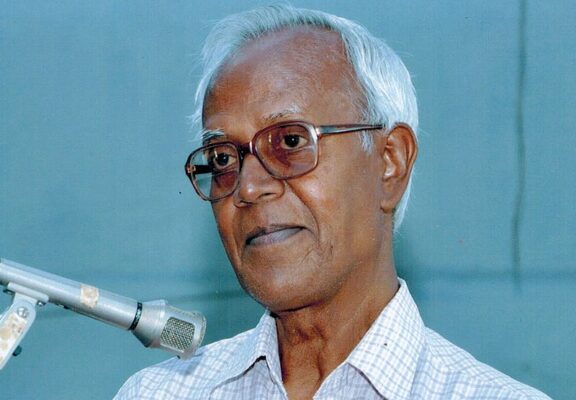

In his video testimony, recorded two days before his arrest by the National Investigation Agency (NIA) on 8 October 2020, Father Stan Swamy said that he was pleased to not be a silent spectator in the face of injustice and was willing to pay the price of dissent.1 Even moments before India’s criminal justice system failed him, Stan was resolute in his belief in the constitution, truth, and justice. I did not know Stan personally, but I feel like I do know him. As a young woman finding my place within India’s civil society, I find Stan embedded in the collective consciousness that drives us all. Stan was emblematic of what democracy means to those of us who fight for it everyday and envision a just world.

For human rights defenders in India, it is easy to be cynical. Father Stan Swamy was special, not only because of his lifelong struggle for India’s most disadvantaged communities—the Dalits and Adivasis, but also because of he love and empathy that drove his struggle. In his tribute to Stan, Arun Ferreira2 recounts that Stan had conditioned himself to eat half a meal as other tribal families around him did, and fifty years of this habit had made his stomach shrink.3 Stan transformed himself to relate to the lived reality of those he worked for; he learned from experience the difficulty of raising slogans on a half-empty stomach. His fight was not easy but his vision was singular—undivided by the institutions that plague India today. Even as a Jesuit Priest, he challenged the Church and religion at large, shunning religious beliefs that did not come to the aid of the people. He fought till the very end for the rights of people—their communities, their land, their rivers and foremost, their freedom of thought.

One day before Stan Swamy breathed his last, the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) directed the Maharashtra state government to make all possible efforts to provide him with medical care.4 However, Stan had already predicted his own death in custody, much earlier than the NHRC cared to notice. On 21 May 2021, Stan had testified before the Bombay High Court and had spoken of his ill health in Taloja Prison. Stating that his health would not improve even if he was transferred to J.J. Hospital, he pleaded to be granted interim bail and allowed to go to Ranchi—his home—before his death.5

The NHRC had been aware of the threats and harassment that Stan had been facing since before his arrest by the NIA. Stan’s house had been raided twice, he was implicated in the Bhima Koregaon case6 without ever having visited the place himself, and he was also charged with sedition in another case by the Jharkhand Police. Human Rights Defenders Alert – India (HRDA), a human rights organisation in India, consistently wrote to the NHRC, seeking intervention and justice for Stan, but the Commission remained unmoved.

On 13 June 2019, for example, HRDA wrote to the NHRC regarding the raid conducted on Father Stan Swamy’s house in Jharkhand by the Maharashtra Police without a valid search warrant.7 More than a year later, on 7 July 2020, the Commission stated that a similar case8 had already been closed on 10 December 2018 and thus, no further intervention of the Commission was required. However, the case that the Commission was referring to relates to the arrests of human rights defenders in connection with the Bhima Koregaon case9 and makes absolutely no mention of the raids conducted on Father Stan Swamy’s residence. Moreover, the case was closed by the Commission solely based on the reports submitted by the Director General of Police of Maharashtra without seeking interventions by civil society members or the accused human rights defenders.

When HRDA wrote to the Commission regarding Stan’s arrest by the NIA on 8 October 2020, it closed the case citing the action report that the NIA had submitted to the Commission.10 The report stated that due procedure was followed in the arrest of Father Stan Swamy and that he “cannot seek any protection or cover in the name of infringement of human rights whereas his act itself is against the security of the state and law”. The NHRC took this comment by the NIA on face value despite being well aware that Father Stan Swamy was a prisoner in pretrial detention whose guilt had never been proven. The NHRC not only overlooked but supported the arrest of an 84-year-old human rights defender and allowed him to be taken from Ranchi to Mumbai during the peak of the pandemic. The report of the NIA was not sent to HRDA for comments, contrary to due procedure, even though HRDA had written to the NHRC about the same on 15 December 2020.

While Stan was in prison, HRDA and other civil society members wrote to the NHRC regarding his failing health, lack of medical attention in prison, risk of contracting Covid-19 and, denial of vaccination to prisoners.11 On 20 May 2021, the NHRC asked for an action report from the Director General of Prisons, Yerawada Central Prison. On 5 July 2021, a reminder was issued to the authority for the report. On 17 August 2021, another reminder was issued to the authority and while sending this reminder the NHRC stated that taking a “lenient view with regard to the pandemic”, the authority had been granted more time to submit the report. It is crucial to observe here that on 5 July 2021, Father Stan Swamy passed away due to lack of healthcare and inhuman prison conditions during the pandemic. In spite of this, the NHRC took a lenient view with authorities citing the pandemic instead of taking up an urgent intervention in favour of his health which was endangered by the pandemic.

The directive issued by the NHRC to the Mahrashtra government on 4 July 2021 to pay adequate attention to Stan Swamy’s health was an act of saving face; doing too little when it was clearly too late. The NHRC took a ‘lenient view’ towards authorities and failed to act where its directives could have made a difference in preventing Stan’s suffering and ultimately saving his life. While Stan was being threatened, raided, falsely implicated in cases in spite of the lack of credible evidence, forced to travel during the pandemic and inching closer to death in Taloja prison, the NHRC repeatedly delayed urgent interventions in the matter. The NHRC did not follow its own Practice Direction 17 in sending reports by authorities to the complainants for their comments, nor did they send reminders to authorities to taking urgent actions on the issue. In fact, the NHRC closed cases based on reports submitted by concerned authorities, rather than independently investigating the allegations made by civil society.

It is clear that in the fight to save Stan, the NHRC stood firmly with the state that incarcerated him, rather than following its mandate to actively protect human rights defenders from reprisals.

The injustice meted out to Stan reminds me of India’s last Mughal Emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar. For his participation in the revolt of 1857, Zafar was charged with treason, exiled to Burma, and buried in an unmarked grave after his death. His last wish, that to be buried in Mehrauli, in his home and country, was not fulfilled by the British. He wanted to spend his last days in prison writing poetry, but the British denied him pen and paper. We had expected this cruelty from our colonizers. Our ancestors fought hard against this cruelty, and I don’t think they would have fought so hard if they could see the country as it stands today. A country where a man like Stan Swamy, who spent his life fighting for the ideals that independent India was built upon, was falsely accused for his human rights work, harassed, imprisoned, denied warm clothing and even a straw and sipper cup which would have assisted him due to his advanced Parkinson’s disease, denied a chance to visit his home before his death, and denied the last chance to walk as a free man. We had expected this tyranny from our oppressors, but not from a government that we willed into power.

The Indian state is responsible for the persecution, arrest and ill-treatment in custody of Father Stan Swamy which resulted in his death. However, these acts of persecution are representative of something larger; a state that wants to continue to persecute and exploit the Dalit and Adivasi minorities. A state that does not want them to be aware of their rights, lest they start demanding them. A state that intends to continue the disenfranchisement of its communities and will persecute anyone who dares to showcase these injustices to the world. The people that Stan worked tirelessly for have lost their voice yet again; first the state took away their rights, then took their land, and in the end, it took their spirited leader. Stan will remain, however, as powerful in death as he was in life; his courage, empathy, and unwavering commitment to justice will continue to be an inspiration to those who had the privilege to know him in life and to those who are only now starting to know him and his legacy.

Note on the author: Prachi Lohia is an independent researcher in the field of human rights

Article: A version of this article was carried by The Wire (India) on 5 July 2022, marking the 1st anniversary of Stan Swamy’s death in custody. The article is republished here with the author’s permission.

Footnotes

1 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KNVibqUVZDU

2 Arun Ferreira is a human rights lawyer who has been a member of the Committee for Protection of Democratic Rights and the Indian Association of People’s Lawyers. He is one of the co-accused in the Bhima Koregaon case, along with 15 other human rights defenders and is currently in prison.

3 https://scroll.in/article/1002315/how-the-system-broke-stan-swamy-a-cell-mate-recalls-the-activists-last-days-in-prison

4 https://nhrc.nic.in/media/press-release/nhrc-asks-maharashtra-chief-secretary-ensure-every-possible-medical-treatment

5 https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/activist-stan-swamy-seeks-interim-bail-says-he-cant-walk-or-eat/article34613077.ece

6 Since June 2018, 16 well known HRDs have been jailed under charges related to terrorism in the Bhima Koregaon case and denied bail. The case relates to violence that took place in Bhima Koregaon, Maharashtra State, on 1 January 2018. The accused – Sudhir Dhawale, Rona Wilson, Shoma Sen, Mahesh Raut, Surendra Gadling, Sudha Bhardwaj, Arun Ferreira, Vernon Gonsalves, Varavara Rao, the late Stan Swamy, Anand Teltumbde, Gautam Navalakha, Hany Babu, Jyoti Raghoba Jagtap, Sagar Tatyaram Gorkhe, and Ramesh Murlidhar Gaichor – are well-known for their commitment to the human rights of the most vulnerable and oppressed, particularly Dalit and Adivasi communities, and have been labeled by the authorities as terrorists, subjected to deliberate misinformation campaigns, and repeatedly denied bail despite their age and the risks posed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

7 Case no. 739/34/16/2019

8 Case no. 1618/13/23/2018

9 On 28 August 2018, five human rights defenders were arrested by the Pune police in different parts of India. Sudha Bhardwaj, Vernon Gonsalves, Varavara Rao, Gautam Navlakha and Arun Ferreira were all arrested in different cities under a host of charges, including terrorism-related charges.

10 Case no. 1036/34/16/2020

11 Case no. 1033/13/0/2021