SOURCE: LatAm Dialogue

AUTHOR: Jim Loughran

When the disappearance and murder of British journalist, Dom Phillips and Brazilian indigenous rights defender, Bruno Pereira spread across international media in June 2022, it may have seemed that this incident was another random killing in Brazil; a country beset by poverty, inequality and a climate of violence. The reality, however, is that the bullets that killed Dom and Bruno did not originate that day on the banks of the Amazon, but travelled from Brasilia to the state of Amazonas. These brutal killings were the inevitable consequence of the Brazilian government’s policies designed to exploit the country’s natural resources, prioritise private economic interests, and intimidate as well as silence critical voices. The government has, through various policies and messaging techniques created a climate in the country in which certain individuals feel emboldened to attack and often murder human rights defenders.

Since being elected in January 2019, Bolsonaro has stayed true to his election promises including that he “would not grant one more centimetre of land to indigenous peoples”, that he would “develop the resources of the Amazon”, “purge leftists from government”, and “end affirmative action in Brazilian universities”. From day one he has facilitated a corrupt, authoritarian system that gives free rein to land grabbers as well as illegal miners and loggers. He has given the green light for the illegal occupation and exploitation of public and indigenous lands and removed many of the legal protections for indigenous peoples. He has even described human rights groups working in the Amazon as a “cancer” that he “can’t kill”. He has used the courts to stifle critical voices — including journalists, politicians, Indigenous leaders and activists — many of whom have been investigated under the dictatorship-era National Security Law, which is widely considered unconstitutional. While traditionally Brazil has a well-developed system of environmental protection, Bolsonaro has worked systematically to undermine it, introducing at least 57 pieces of legislation to reduce environmental protection.

At all levels of the political system key officials charged with implementing environmental protection legislation have been removed and replaced with police or army officers. The politically motivated dismissal of indigenous rights expert Bruno Pereira is a case in point. In 2019, Bruno was unceremoniously removed from his position in FUNAI (the government agency established to protect indigenous rights), following his successful campaign to shut down one of the largest illegal mines in the country, which had been operating in Roraima state in an area reserved for the Yanomami people.

The Yanomami reservation in Roraima and Amazonas is the largest indigenous reservation in Brazil, covering over 9.6 million hectares; an area the size of Portugal. It is home to the Yanomami and 6 other uncontacted peoples, and because of illegal mining activity, which increased by 46% in 2021, it is on the brink of a humanitarian disaster. According to the Hutukara Yanomami Association, the “illegal extraction of gold [and cassiterite] inside Yanomami territory led to an explosion in cases of malaria and other infectious diseases and a shocking escalation of violence against indigenous people”. Illegal miners reportedly give alcohol and drugs to the indigenous people and their presence has also resulted in a wave of sexual violence.

Further threats come from the Brazilian army building barracks in the Yanomami heartlands. Soldiers have prostituted Yanomami women, some of whom have been infected with sexually transmitted diseases. Indigenous leaders who speak out against the threats to the Yanomami have been put under investigation, including by FUNAI itself, for spreading fake news. In 2021, Sônia Guajajara, the head of Brazil’s largest indigenous organisation, the Association of Indigenous Peoples (Apib), and indigenous rights defender Almir Suruí were put under investigation over social media campaigns raising awareness of the threat that Covid-19 poses to Brazil’s indigenous population. The case against them was eventually dismissed because it was, in the judge’s view, “a legal embarrassment.”

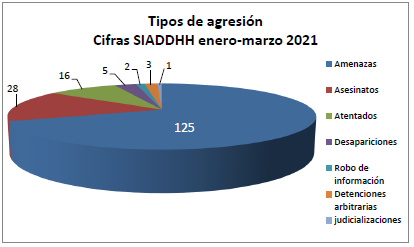

In its Global Analysis 2021, Front Line Defenders reported that “In Brazil, deforestation and mining activities have significantly increased. The protection of natural resources and traditional territories are being neglected as government structures established to safeguard the rights of indigenous peoples and the environment are being dismantled and weakened. Attacks against and killings of Human Rights Defenders (HRDs), indigenous peoples, members of Quilombolo (Afro-descendent) communities and environmental defenders have increased”.

This stigmatisation of human rights defenders and the dismantling of legal protections by the current administration has had deadly consequences. As Senator Randolfo Rodrigues, who is in charge of the investigation into the murder of Dom Phillips and Bruno Pereira, said recently: “Jair Bolsonaro’s demolition of Brazil’s Indigenous and environmental protection services and surrender of the Amazon to crooks played a direct role in the murders. Jair Bolsonaro spoke about not surrendering the Amazon – but he has surrendered it to the worst kind of banditry there is”.

While Bruno and Dom’s killing made headlines around the world, it is distressing to note that, in most cases, the names of killed indigenous and human rights defenders will never appear in print, and almost 100% of the killings remain in impunity. Killers target indigenous leaders safe in the knowledge that after an initial flurry of publicity the investigation will dry up and the case will be filed away.

An example is the story of indigenous leader and human rights defender Zezico Rodrigues Guajajara who was shot dead as he was driving a motorbike near his home village in Maranhao in late March 2020. To this day, no one has been brought to justice for the killing. A member of the Guajajara people, he had worked for years to protect land in the Amazon belonging to his ancestors and other uncontacted, or isolated, indigenous peoples. For Zezico, fending off illegal incursions on indigenous lands had become increasingly dangerous as emboldened logging and mining groups, who feel they have been given a green light by Bolsonaro, targeted him and other Indigenous environmental activists. He was the fifth Guajajara to be killed in a five-month period and one of over two dozen forest protectors killed in Brazil since 2019.

This is a pattern of violence that is repeated across the Amazon. In order to prevent invasions of their territory and illegal exploitation of the rainforest, the Ka’apor indigenous people have established zones of protection and agro-forestry production in areas bordering indigenous land, near clandestine roads opened by illegal miners and loggers. Despite the fact that this work has contributed to an 80% recovery of the degraded areas of forest, the Ka’apor have been repeatedly attacked by the miners and loggers. Bolsonaro sees the protection of indigenous rights and land as an obstacle to economic development. In April 2019 he provoked an international backlash when he stated: “Let’s use the riches that God gave us for the well-being of our population. You won’t get any trouble from the Environment Ministry, nor the Mines and Energy Ministry nor any other because our ministries, for the first time in the Republic, all understand and speak the same language: A better Brazil for all of us.”

In 2020, the Comissão Pastoral da Terra (CPT) Documentation Centre – Dom Tomás Balduino recorded 18 deaths as a result of rural conflicts, and in 2021, recorded 35 deaths; an increase of 75%. The Human Rights Defenders Memorial project which documents the killings of human rights defenders worldwide has reported the killing of 16 indigenous rights defenders in Brazil between 01 January 2019 (when Bolsonaro took office) and the end of 2021.

With elections looming in October 2022, Bolsonaro’s continued war on environmental protections is threatening the very existence of indigenous peoples in the Amazon as well as the people trying to protect these areas. It is imperative that Brazil’s international partners and investors send a clear signal that all financial and political support for Brazil is dependent on respect for the democratic process and commitment to a clear, rights-based programme of legal and social reform.

According to Global Witness, 39 indigenous rights defenders were killed in Brazil between 2016 and 2021. These killings have been accompanied by a devastating increase in deforestation which increased 74% in the period 2018/19 and yet, according to Amnesty International, the Brazilian programme to protect defenders “has not introduced any mechanisms for the meaningful participation of civil society; has not yet managed to minimally develop a comprehensive policy of protection that includes gender and racial perspectives and the needs of groups and collectives; and has failed to ensure the implementation of state-level protection programmes.” The protection of the indigenous rights defenders in the Amazon would be a good place to start. So far, Bolsonaro’s administration has not only failed to protect indigenous and human rights defenders but is actively putting them at risk.

Sources:

NPR – A Violent Tragedy Foretold in the Amazon

https://www.npr.org/2022/06/17/1105852069/opinion-dom-phillips-bruno-pereira-brazil-amazon-environmental-crime?t=1661612996602

IACHR – Human Rights in Brazil – 2021

chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/http://www.oas.org/en/iachr/reports/pdfs/Brasil2021-en.pdf

HRW – Brazil: Indigenous rights Under Serious Threat

https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/08/09/brazil-indigenous-rights-under-serious-threat

HRW Letter on the Amazon and its Defenders to the OECD

https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/02/06/letter-amazon-and-its-defenders-organisation-economic-cooperation-and-development

Folha da Sao Paulo

https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/internacional/en/brazil/2022/06/bruno-pereira-dead-at-age-41-left-his-position-to-work-with-indigenous-people-in-the-amazon.shtml

The Hutukara Yanomami Association

Davi Kopenawa / Hutukara Yanomami Association – Right Livelihood

The Guardian – Brazil targets Indigenous leaders

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/may/13/brazil-police-indigenous-leaders-covid-jair-bolsonaro

Front Line Defenders – Global analysis 2021

2021_global_analysis_-_final.pdf (frontlinedefenders.org)

The Guardian – Bolsonaro Hands amazon to Criminals

Bolsonaro’s ‘surrender of Amazon to crooks played role in murders of Phillips and Pereira’ | Jair Bolsonaro | The Guardian

Mongabay – Killings of Indigenous Leaders Hit Highest Levels in Two Decades

https://news.mongabay.com/2019/12/murders-of-indigenous-leaders-in-brazil-amazon-hit-highest-level-in-two-decades/

Front Line Defenders – Concern over Increased Attacks on Ka’apor people

https://www.frontlinedefenders.org/en/statement-report/concern-over-escalation-attacks-and-intimidation-against-kaapor-indigenous-people

CPT – Massacres no Campo

Comissão Pastoral da Terra – Conflitos, Massacres e Memória dos Lutadores e Lutadoras do Cerrado (cptnacional.org.br)

Amnesty International – Brazil: Human Rights Under Assault

Brazil: Human rights under assault: Submission to the 41st session of the UPR working group, 7 – 18 November 2022 (amnesty.org)

Voice of America -Brazil Indigenous Expert Was 'Bigger Target' in Recent Years

https://www.voanews.com/a/brazil-indigenous-expert-was-bigger-target-in-recent-years/6623195.html

Global witness Brazil Report

https://www.globalwitness.org/en/all-countries-and-regions/brazil/