Aunque la tasa general de homicidios disminuyó con el acuerdo de paz, la violencia se ha enseñado contra quienes defienden los derechos de los más vulnerables- es decir contra los mismos que sufrieron la guerra-. ¿Qué está pasando y qué se puede hacer?

Author Carlos Guevara

Source Razón Pública

Los salmones

Siempre he sentido fascinación por los salmones. Me asombra su capacidad de afrontar obstáculos y vencerlos. Los salmones enfrentan un sin fin de depredadores durante meses y en el momento culmen de su vida, nadan contra la corriente para poder reproducirse.

La vida de los líderes sociales en Colombia se asemeja a la de este pez extraordinario.

Durante décadas, los líderes sociales fueron la población más invisibilizada del conflicto armado. Tanto así que ni siquiera el Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica los mencionó en su principal documento, el informe Basta Ya. Han sido olvidados por el Estado colombiano en su conjunto. Los gobiernos de turno de los últimos 20 años han hecho todo lo posible por ocultar la violencia sistemática que sufren los líderes sociales de Colombia.

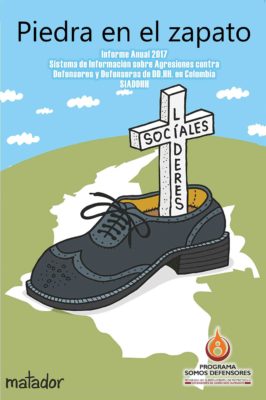

Desde la sociedad civil, el registro más antiguo de violencia contra líderes sociales es el del Centro de Investigación y Educación Popular (CINEP). Pero la documentación más precisa la tiene el Programa Somos Defensores, que cuenta con la base de datos más completa y donde se registran aproximadamente cinco mil defensores y defensoras de los derechos humanos que han sido agredidos.

Los diversos gobiernos de los últimos 20 años han hecho todo lo posible por ocultar la violencia estructural que sufren los líderes sociales.

Esta invisibilidad, que parecería ser lapidaria para los líderes sociales, no ha sido excusa para que estos “salmones” sigan adelante. En medio de la guerra, estos activistas en los ámbitos local, regional, nacional e internacional izaron la bandera de la salida negociada del conflicto como única forma de acabar con las hostilidades y así buscar un país distinto.

Hace veinte años comenzamos a oír de los “defensores de derechos humanos” gracias a la declaración de Naciones Unidas donde se definía quiénes eran estos activistas y se establecían las obligaciones de cada Estado miembro con estos hombres y mujeres.

Pero en Colombia ya los conocíamos, aunque con otros nombres: los llamábamos líderes campesinos, indígenas, afros, sindicalistas, líderes estudiantiles, feministas o ambientalistas. Claro está, una pequeña pero poderosa fracción de la población colombiana los llamaba de otras formas peyorativas: chusmeros, mamertos, revoltosos, guerrilleros, terroristas.

El pasado 27 de enero, el líder social y defensor de derechos humanos Temístocles Machado fue asesinado en Buenaventura por sujetos todavía desconocidos.

Hoy, a pesar de los años y del avance de la democracia, la ampliación del paquete de derechos humanos y la firma de un acuerdo de paz con la guerrilla más antigua del continente, los “salmones” se siguen muriendo, pero no de viejos.

2017: más violencia focalizada

Ministro de Defensa, Luis Carlos Villegas

Foto: U.S Department of Defense |

La implementación de los acuerdos de paz con las FARC tiene un sabor agridulce. Si bien es de suma importancia reconocer que el silencio de los fusiles implicó que tuviéramos la tasa de homicidios más baja en los últimos 30 años —24 por cada 100 mil habitantes—, esa tasa de homicidios se disparó focalizadamente en los defensores y defensoras de los derechos humanos.

Según cifras del Programa Somos Defensores los homicidios contra estos activistas vienen en aumento sostenido desde que empezó el proceso de paz:

- En 2013 hubo 78 casos

- En 2014, 55 casos

- En 2015, 63 casos

- En 2016 80 casos

En 2017 la cifra rompió la barrera de los 100 casos y en 2018 la situación no mejora y se torna aún peor con un registro de 18 líderes asesinados en los primeros 31 días del año.

De estos homicidios recientes de 2017 y lo que llevamos de 2018, los activistas con mayor número de muertes son los líderes campesinos, comunitarios, de juntas de acción comunal e indígenas en zonas rurales. Esto muestra que la violencia se concentró en personas defensoras pobres de lugares apartados del país donde la guerra ha estado siempre: departamentos como Antioquia, Norte de Santander, Valle de Cauca, Cauca, Nariño, Meta, Córdoba y Chocó.

Son personas con pocas posibilidades de acceder a la ayuda estatal: la misma población que ha puesto los muertos de esta guerra que no termina.

La violencia se focalizó en personas pobres de lugares apartados: la misma población que ha puesto los muertos de esta guerra que no termina.

Es aquí donde surge la pregunta del millón: ¿quién los está matando? Hay un mar de dudas.

Según la medición histórica de Somos Defensores, los mayores asesinos siguen siendo desconocidos (en parte por la inmensa impunidad, que llega al 87 por ciento según el informe especial STOP WARS – Paren la Guerra contra los defensores), seguidos de grupos de ascendencia paramilitar y con participaciones en menor proporción de fuerzas de seguridad del Estado y guerrillas.

Para las autoridades, los responsables de estos crímenes son de distintos tipos y por diversas motivaciones, como lo señaló el Fiscal General Néstor Humberto Martínez o incluso por “líos de faldas”, como lo dijo el Ministro de Defensa Luis Carlos Villegas. Infortunadamente, ambos funcionarios desconocen de tajo las motivaciones políticas que desde siempre han estado detrás de estas muertes y que aún no son investigadas a profundidad.

Más de 70 personas han sido capturadas por los crímenes de 2016 a 2018, pero ninguna de ellas corresponde a autores intelectuales sino tan solo a los que halaron el gatillo.

Un río de desafíos

Líderes sociales.

Foto: Gobernación del Atlántico |

En ese contexto, los “salmones” enfrentan el desafío de ser la pieza clave en la puesta en marcha de los acuerdos de paz, pues son ellos quienes tienen los contactos, el conocimiento de terreno y de las comunidades así como la experiencia organizativa y de vida para hablar de paz en medio de la guerra soterrada que aún los golpea.

Ellos fueron ellos quienes entre 2014 y 2017 lograron la movilización política de las víctimas, el avance en políticas estatales de derechos humanos y de protección, el no estancamiento de espacios tripartitos (Gobierno – Comunidad Internacional – Sociedad Civil) para garantizar la vigencia de los derechos humanos en Colombia e hicieron grandes contribuciones a las mesas de La Habana y de Quito.

El Estado colombiano tiene un río de desafíos para garantizar que los defensores sigan vivos y haciendo su trabajo:

1. Protección: Los mecanismos de protección existentes (decreto 1066 de 2015 y su programa de protección a personas en riesgo) y los derivados de los acuerdos de paz (Comisión de Garantías de Seguridad y No Repetición) aún no acaban de armonizarse.

El gobierno sigue protegiendo con escoltas, chalecos antibalas, vehículos blindados y teléfonos celulares, pero la protección colectiva, que es la que realmente se necesita, aún no despega muy a pesar de tener un decreto reglamentario (decreto 2078 de 2017).

Todo en el papel se ve bonito, pero a la fecha no hay dinero suficiente para cubrir semejante desafío. Actualmente, el Estado protege a 9 mil personas y en ello invierte más de 150 millones de dólares al año. El desafío es proteger nada menos que a 15 mil personas. Tampoco existe la capacidad institucional para atender el volumen de solicitudes de protección por venir.

No hay dinero suficiente para los líderes sociales, ni existe una institucionalidad preparada para dar abasto a las solicitudes de protección.

2. Prevención: Si bien el decreto 1066 de 2015 y su programa de protección a personas en riesgo dicen que el componente de prevención de esas violencias es fundamental, en la realidad nunca se han podido adoptar mecanismos eficaces para hacerlo.

Los mecanismos existentes, como el Sistema de Alertas Tempranas (SAT), no son tomados con la seriedad necesaria por el gobierno. Ejemplo de ello es el Informe de Riesgo 010 – 17 emitido el año anterior donde se advertía sobre el peligro que corrían más de 200 organizaciones de derechos humanos y sus activistas en 24 departamentos del país, sin que a la fecha se sepa qué hizo el gobierno para atender esta advertencia.

En el nuevo escenario de post acuerdo, el componente de prevención deberá ser una prioridad si no queremos seguir contando defensores muertos. Para lograrlo, ya hay un nuevo decreto (decreto 2124 de 2017) que podría fortalecer la autonomía y eficacia del SAT. Amanecerá y veremos si se logra.

3. Investigación: Si bien hay que reconocer que en 2017 la Fiscalía avanzó como nunca antes en las investigaciones por crímenes contra defensores, falta avanzar en análisis sobre esta violencia y sobre los posibles patrones comunes entre estos crímenes.

Es muy positivo que el Fiscal General haya reconocido que hay indicios de “sistematicidad” en los asesinados de defensores, pero esta posición debe redundar en investigaciones profundas que develen los planes y organizaciones criminales detrás de estas muertes.

Solo cuando el salmón logra desovar en aguas más tranquilas, río arriba, descansa de su largo trayecto y recuerda que el camino que enfrentó recorrió y venció es la garantía de que sus descendientes tengan una oportunidad de vivir.

Así también los defensores de derechos humanos y líderes sociales han recorrido un largo camino hasta llegar a esta paz negociada con la esperanza de que sus descendientes y en general, sus propias comunidades, tengan esa oportunidad de conocer un país con menos dificultades para vivir en paz.

Colombia tiene la responsabilidad de estar a la altura de esa misión.

* Carlos Guevara es Coordinador de Comunicaciones, Incidencia y Sistema de Información de Derechos Humanos (SIADDHH) del Programa Somos Defensores, máster en Comunicación Política y Empresarial, especialista en Dirección de Cine, Video y TV, comunicador social y periodista.